Columbia Scientists Expect Record El Niño

Massive fires in Indonesia. A typhoon in the Philippines. Forecasts of flooding in Kenya, drought in Brazil and torrential rains in bone-dry Southern California.

These disasters are separated by thousands of miles and on different continents, but they have a common cause—the climate phenomenon known as El Niño.

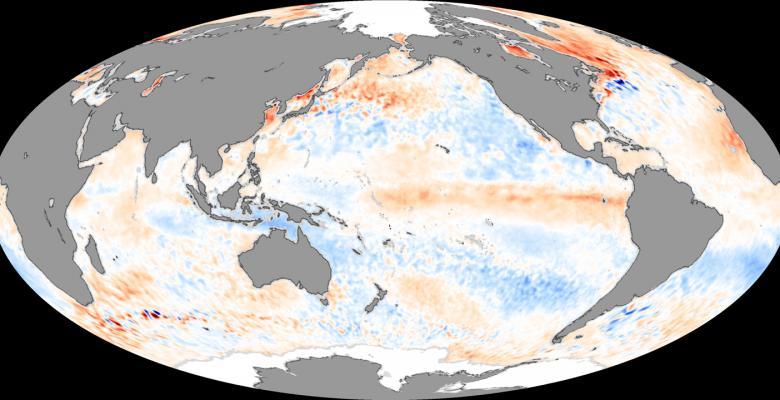

It occurs every two to seven years, as surface-water temperatures rise in the eastcentral Pacific near the equator and trade winds—which normally blow westward— diminish. Warmer ocean water—which can then push eastward—increases temperatures in the atmosphere, leading to further warming and climate disruptions around the globe. Some areas are inundated with rain while others suffer droughts.

El Niño is independent from climate change, although the effects may combine to become stronger than either alone, and this year is already on track to be the warmest on record. “It’s an open scientific question whether the average climate will look more like El Niño in the future, whether some of the things we’re seeing now will happen more frequently,” said Adam Sobel, professor of earth and environmental sciences and director of Columbia’s initiative on climate and extreme weather.

“That we can now say what to expect months in advance is a real success of climate science.”

— Professor Adam Sobel

“There’s a chance this El Niño will be the biggest, or among the three biggest, on record,” said Anthony Barnston, lead forecaster for Columbia’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI).

That forecast is based on sea surface temperatures in the central equatorial Pacific. Any increase greater than 1.5 degrees Celsius is considered strong, and this year the temperatures are already 2 degrees Celsius above average, weeks before El Niño typically peaks in December. When in late 1997 the temperature reached 2.5 degrees above average, it led to the biggest El Niño since 1950, when the first detailed records began.

Barnston and Sobel are among more than 200 researchers at Columbia studying climate in general and El Niño in particular. Mark Cane, the G. Unger Vetlesen Professor of Earth and Climate Science at Columbia’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and his then-graduate student, Stephen Zebiak, developed the first computer model to successfully predict El Niño in the 1980s.

El Niño means “little boy” in Spanish; the name comes from South American fishermen who noticed that water temperatures tended to rise at the end of the year, near Christmas, and started calling the phenomenon “boy child” after the baby Jesus.

Although it has been happening for centuries, modern technology has made forecasting possible. “That we can now say what to expect months in advance is a real success of climate science,” said Sobel.

Related: El Niño 2015 Conference with Livestreaming

IRI, which began as a pilot project following the first international conference on forecasting El Niño in 1995, works with developing countries to help them anticipate and manage climaterelated events. This month climate scientists from around the world are gathering on the Lamont campus for a conference hosted by IRI and sponsored by the World Meteorological Organization, the U.S. Agency for International Development and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and others.

Governments, especially in developing countries, often don’t have the resources to undertake costly preparations, said Lisa Goddard, senior research scientist and IRI’s director. Among organizations represented at the conference will be the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent and the United Nations World Food Program. “There’s a need to build information and communication to support what they’re doing and to strengthen the networks they have in place.” said Goddard.

The economic impact of an El Niño can be huge, especially in countries dependent on agriculture. Asia was the first to feel this year’s El Niño effects. Heavily polluted air from fires in Indonesia is keeping people indoors, even in nearby Singapore. In coming months, the effects of El Niño will spread east to the Americas and then Africa, ending next spring.

El Niño’s impact on crop yields for rice and other staples pushes up food prices and can affect nutrition, especially in the developing world, said Madeleine Thomson, a senior research scientist at IRI who studies the health impacts of climate. Floods can increase the incidence of diseases transmitted by insects such as malaria and dengue fever in east Africa, she added.

In the U.S., heavy rains in Southern California may cause mudslides, but the wet weather may not extend far enough north to fill reservoirs and end the recent drought, said Barnston. Heavy rains are expected throughout the southernmost states, including Texas, Louisiana and Florida, while the Pacific Northwest may be drier than usual.

Although some reports linked recent mudslides in California and Hurricane Patricia to El Niño, Barnston said that the Americas won’t feel the full effects of El Niño until December or January.

A strong El Niño is often followed by a reverse phenomenon known as La Niña, when surface temperatures in the Pacific are cooler than normal; places that are wetter than normal during an El Niño are dry, and areas of drought have heavy rain.

“I tell people planning a winter vacation during an El Niño to avoid Florida and go to Hawaii instead, where it is dry,” said Barnston. “During La Niña they should go to Florida and avoid Hawaii.”